Before moving on to the next approach to the problem, this post presents code — functions — in the programming language Julia that automate the row and column methods of the first two posts.

In addition, these functions generalise to any positive number of days n. This will come in handy in the event that we are ever invaded by an alien species or artificial general intelligence is achieved, and our alien or robot overlords command that there should be say, 100 days, instead of 12 days of Christmas. 🙂

When I first wrote this post, I included examples in the R and Python languages in addition to Julia, an emerging language that’s gaining popularity, especially in scientific computing which has been dominated for decades by Fortran, MATLAB, R, Python and a handful of other languages.

In the end I decided that presenting examples in just one language was best since it avoids arbitrary differences between languages and, frankly, some languages have counter-intuitive constructs, all of which serves only to distract from the main point of the post.

For the first method in part 1, summing all the gifts received per day and adding all the the resulting values (the green column of the table in part 2), looks like this in mathematical notation:

- The variable i below the right sigma (summation) symbol takes on values from 1 to day, all of which are added, leading to the day totals in the green column of part 2’s table (shown below again).

- The left summation corresponds to the addition of each day total number in the green column to arrive at the final gift total in purple.

The table from part 2 is shown here for reference:

Here is a Julia function, daysofxmas, that is one possible implementation of this notation, taking a parameter n and returning the total gifts received in n days. Invocations of the function where n is 12 and 100 are shown. The line with “# 1” is a comment. I’ll use this to number distinct functions for reference.

- The for loop corresponds to the left-most summation in the mathematical notation,

- sum(1:day) corresponds to the right-most summation in which each whole number from 1 to day is added and assigned to the variable daysum, and

- each day’s sum is accumulated in the variable total which is returned from the function.

# 1

function daysofxmas(n)

total = 0

for day in 1:n

daysum = sum(1:day)

total += daysum

end

total

end

julia> daysofxmas(12)

364

julia> daysofxmas(100)

171700

171,700 is obviously a lot of gifts and we wouldn’t want to have to add all those gifts per day by hand! 364 is bad enough.

Adding a formatted print call to the function shows day number, sum of gifts per day, and cumulative total, after which the final total is printed, as before. The weird-looking formatting strings (e.g. %2i) tell Julia how many spaces a number should occupy (2 or 3 here) in the output and what type of numbers to expect (integers, i.e. whole numbers).

using Printf: @printf

function daysofxmas(n)

total = 0

for day in 1:n

daysum = sum(1:day)

total += daysum

@printf("%2i: %2i => %3i\n",

day, daysum, total)

end

total

end

julia> daysofxmas(12)

1: 1 => 1

2: 3 => 4

3: 6 => 10

4: 10 => 20

5: 15 => 35

6: 21 => 56

7: 28 => 84

8: 36 => 120

9: 45 => 165

10: 55 => 220

11: 66 => 286

12: 78 => 364

364

Two for loops could have been used instead, which has the advantage of matching the notation’s summation structure more explicitly, but requires a bit more code and is not as fast as the first implementation above (which we’ll return to below).

# 2

function daysofxmas(n)

total = 0

for day in 1:n

daysum = 0

for i in 1:day

daysum += i

end

total += daysum

end

total

end

Instead, a more compact form of this function uses a language feature known as the list comprehension. Here, the inner sum yields a list of per-day gift totals, which the outer sum adds up (again, the green column of the table in part 2).

# 3

function daysofxmas(n)

sum([sum(1:day) for day in 1:n])

end

This is faster than function #2 and about the same as #1. It is also a close match to the mathematical sigma notation above, represented as Julia code.

In addition, it is more declarative, allowing us to focus more on expressing what we want to do rather than how. Another advantage is that it allows a programming language like Julia to have better control over what to optimise for best performance.

Building up the expression returned from line 3 in stages with n = 12, makes it easier to see what’s going on, if you are interested in the detail:

julia> [day for day in 1:12]

12-element Vector{Int64}:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

julia> [sum(1:day) for day in 1:12]

12-element Vector{Int64}:

1

3

6

10

15

21

28

36

45

55

66

78

julia> sum([sum(1:day) for day in 1:12])

364

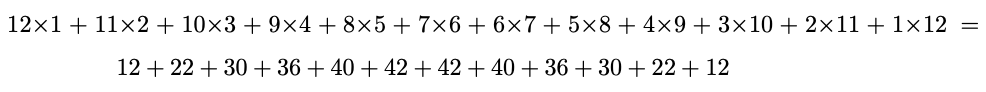

Now recall the second method presented in part 2: the result of summing the blue cells in the table, where each corresponding value in the sequences 1, 2, …, 12 and 12, …, 2, 1 is multiplied, with the products then being added:

In mathematics, this is known as the dot product:

Again, 12 can be generalised to n:

The following Julia code defines an implementation of the function daysofxmas that carries out this particular dot product.

Again, invocations of the function where n is 12 and 100 are shown.

#4

function daysofxmas(n)

days = [1:n;]

sum(days .* reverse(days))

end

julia> daysofxmas(12)

364

julia> daysofxmas(100)

171700

[1:n;] means: generate a sequence, a vector, of all the whole numbers from 1 to n.

Use of the reverse function here can be replaced by [n:-1:1;] which says: give me a vector of all the whole numbers from n to 1, where -1 means “step -1”, i.e. start from n and count down by 1, stopping at 1. The end result is the same.

All of the functions presented here yield their result in a tiny fraction of a second, even for a silly 1000 or 10,000 days of Christmas (166,716,670,000 or more than 166 billion gifts), both of which would require the length of the year to change as well of course!

Even for a truly stupid 100,000 days of Christmas, the time to compute the result (166,671,666,700,000 or more than 166 trillion gifts) is less than a thousandth of a second or better, faster than either Python or R on my Mac (M2 processor, 32 GB RAM).

That is, except for the function definition with the two nested loops (#2), which takes 3 seconds, more than a thousand times slower than all the other function definitions shown. There are good reasons for this that have to do with efficient use of processor resources. I’ll return to this point.

Function #3 could also be modified to implement the shortened form of the calculation, twice the first half of the series, as discussed in part 2: 2 x (12 + 22 + 30 + 36 + 40 + 42), but would need to take into account whether n is odd or even, since a sequence with an odd number of values cannot be split in half such that both halves have the same number of values and the left half is the reverse of the right half. Think of the sequences 1, 2, 3, 2, 1 and 1, 2, 3, 3, 2, 1. The second satisfies this constraint but the first doesn’t.

I was going to avoid that complication, since the code runs fast anyway compared with the effort of manual calculation. But, I couldn’t help myself. 🙂

One implementation of this modification to function #3 in Julia is shown next.

There’s no need to pay too much attention to this code unless you want to. The commentary that remains in this post is the main thing to take note of.

# 5

function daysofxmas(n)

days = [1:n;]

products = days .* reverse(days)

numproducts = length(products)

halflength = div(numproducts, 2)

total = 2 * sum(products[1:halflength])

if isodd(numproducts)

total += products[halflength+1]

end

total

end

This implementation is more complex and this greater code complexity and effort may be misplaced.

Just because one mathematical expression is shorter to write down than another, doesn’t mean that implementing it as a function will make it faster or require less code. For one thing, I’ve had to add more code to take account of the odd-length-check requirement. Most of the code after line 4 is new.

As the famous Computer Scientist, Donald Knuth said:

Well, maybe not all evil, but it’s generally a bad idea to make guesses about whether a different approach will be faster or which parts of your code need to run faster, since your intuition or common sense will very likely fail you. That’s what the discipline of computational complexity and profiling tools are for.

No, not social profiling. Code profiling.

It turns out that when you use a profiling tool on this function, most of the total runtime is spent in the dot product expression: days .* reverse(days). So, working with half of the dot product doesn’t help since it has already been computed.

Any implementation that improves the runtime of #4 or #5 would have to compute the dot product in a different way (e.g. just half of it) or compute it in parallel. Both are possible and I will briefly explore the second of these here, not with the dot multiply implementations of the function (#4 or #5), but with function #2.

Why? Interestingly, it turns out that the slowest definition of the function (#2) we’ve seen so far, the one with two loops and simple addition, can greatly benefit from a parallel implementation.

But to really stress the daysofxmas function, let’s make n = 100,000. A billion days of Christmas! This results in 166,666,667,166,666,667,000,000,000 gifts. That’s 167 million billion billion.

So, how long does this take to run for each function implemented so far? Most

| Function | Time (seconds) |

| #1 | 0.0005 |

| #2 | 24 |

| #3 | 0.0004 |

| #4 | 0.0007 |

| #5 | 0.0007 |

If function #2 is modified in the following apparently minimal way…

# 6

function daysofxmas(n)

total = 0

@simd for day in 1:n

daysum = 0

@simd for i in 1:day

daysum += i

end

total += daysum

end

total

end

…the run-time for a billion days of Christmas becomes 13 seconds!

And, how has the code been changed? A Julia directive (actually a so-called macro) @simd has been added before each for loop. SIMD is an acronym for Single Instruction Multiple Data.

What this means here is that the work of the iterations (for loops) is split up, such that chunks of each vector are operated on by the same machine instructions simultaneously rather than sequentially, i.e. one after another.

This is one example of parallel execution. Note that just randomly adding such a directive to any old for loop won’t necessarily improve the run-time because of code dependencies within the loop. It may in fact make it worse. Such is the case if @simd is added before the for loop in function #1, which roughly doubles the runtime.

Exploring what actually happens when such a directive is added to a language like Julia as well as the nuances of parallel computing is, well, a whole other story.

Is there another implementation that is simpler and competes with #1 or #6 for speed? Yes there is. It turns out to be a minor variation on function #1.

# 7

function daysofxmas(n)

total = 0

daytotal = 0

for day in 1:n

daytotal += day

total += daytotal

end

total

end

Here we use a cumulative day total, remembering all the day additions previously done, only adding the current day number to the day total before updating the overall total. This takes the same amount of time to run for 100,000 days of Christmas as function #1: 0.0005 seconds.

What this last example underscores is that the algorithm matters as dictated by the discipline of computational complexity. Function #7 has time complexity of O(n) which is so-called Big-O notation meaning that there is a simple linear relationship between the number of days of Christmas, n, and the time it takes to compute the number of gifts. This is in contrast with function #2 that has a time complexity of O(n2) such that the time taken to compute the gifts for n days is the square of n, which for large n can get big very quickly, e.g. for n = 10,000, n2 is 100,000,000 instead of just n.

As an aside, #4 and #5 use more computer memory than all the other functions, because of the large vectors they hold in memory.

But enough of this!

Back to the mathematics (and a bit of code) in part 4, but still very much continuing down the path to generalisation and brevity.